The unknown story of Harriet Macmillan Cockburn

By David Bruneau, Emma Smelten (université de Picardie Jules Verne, France) and Aleksandar Jekic, Matija Palčič (University of Ljubljana, Slovenia)

Harriet Macmillan Cockburn (03.09.1873 Toronto, Canada – 16.12.1948 in Toronto, Canada) was a Canadian humanist and doctor, serving in the third unit of the Serbian Relief Fund.

Cockburn grew up in Toronto, where she also graduated from Trinity College with a medical doctorate (Trinity College, 1922, p. 38). After working in India, she initially planned to go back to Canada. Unfortunately, there is no further information in sources about her that explain where and why she was working in India. However, after her work in India, more precisely during a stay in Paris on her way back to Canada, she got informed about the call for help of the Serbian government, after which she immediately went to Serbia, where her activities are better reserved in public sources. Nevertheless, her case remained unknown and is still rather unexplored. Some attention came up through research of the Serbian diaspora in Canada, that started to investigate the activities of Canadians in Serbia during world war I after noticing that Canadian volunteers were mentioned in the war memories of high rank officials of Serbia.

The increasing interest of the diaspora resulted in an exhibition under the name “Kanađani, hvala vam”, translatable as ‘Canadians, thank you”, that was held in Belgrade and Toronto and inter-alia outlined some key events in Cockburn’s life (vesti, 2015).

However, in contrast to other volunteers in Serbia with the same rank, like Flora Sanders, she did not receive the same amount of attention, which is why documents that deal with her life remain barely and no streets or monuments are named after her.

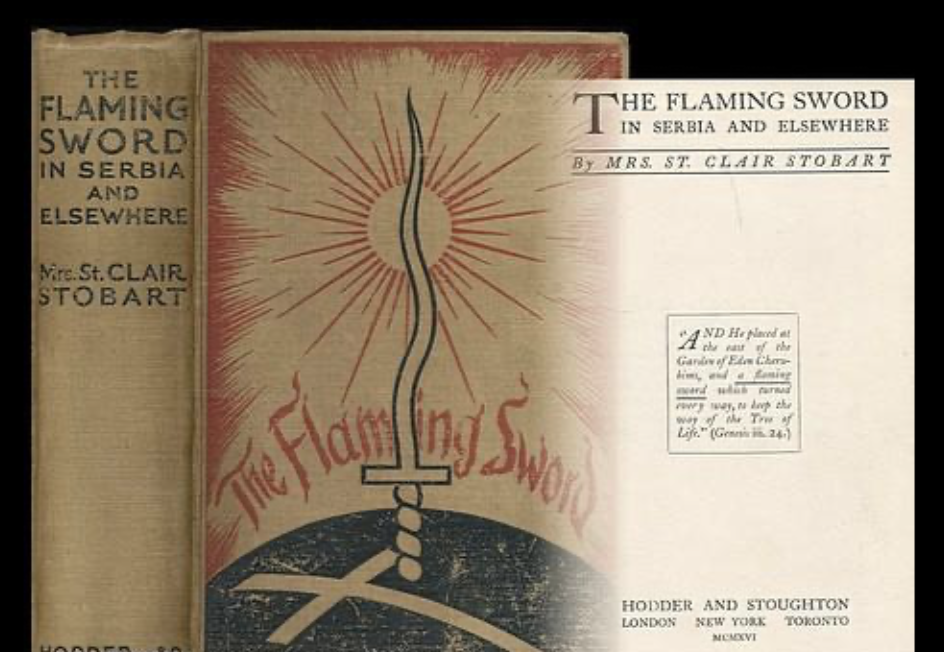

Coming back to her case, the already mentioned call for help was published in 1915, after Serbia lost over 50.000 soldiers and 150.000 civilians. During the war over 600 Canadians voluntarily joined the Serbian army. Cockburn worked in a hospital in Lapovo in a unit of 16 voluntaries, a strategic important city between Belgrade and Niš, close to Kragujevac in the central part of today’s Serbia. The hospital was placed in two barracks which encompassed 146 beds (Hart, 1916). It was part of the Stobart’s Unit of the Serbian Relief Fund, which was initiated by the Red Cross in order to help the Royal Serbian army with dealing with the outbreak of typhus. In the book “The flaming sword in Serbia and Elsewhere”, where the memories of Mabel Annie Stobart, the head of the Stobart unit, are published, Cockburn is also mentioned as a doctor that gained the sympathies of the soldiers (Stobart, 2004, p. 88).

In general, world war I was characterized by specific roles that were attributed to woman and medical staff. Medical staff were ascribed with paradoxical characteristics. On the one hand, they were also seen as heroines, idealizing them as avatars of the Virgin Mary. On the other hand, writings from woman in the world war I did not receive the same attention as the works of man. They were perceived as inferior in comparison to the writings of soldiers that were seen as the only legitimate actor in the war (Brasme, 2021, p. 1). This underestimation of the role of woman in world war I is also captured in the already mentioned book of Stobart, in a scene that even deals with Cockburn:

“Dr. Cockburn, a Canadian doctor, at once won the sympathies of the peasants, who came in hundreds to the dispensary. The first patient, however, gave her much amusement. He was a Serbian officer; he asked to see the doctor, and when she said that she was the doctor, he ran away, and he never came back.” (Stobart, 2004, p. 88).

Furthermore, Cockburn is not only mentioned in Stobart’s book, but also had the possibility to share her memories and impressions about her time in Serbia in an article that was published by the newspaper Toronto World on 5 March 1916. In 1915, she witnessed the continuous retreat of the Serbian forces, which is why she received an order to leave already in October 1915. Thereby, she experienced one crucial moment in Serbian history: the Great Retreat or Albanska Golgota, a strategic withdrawal which included 400.000 people that aimed to reach the Adriatic coast in order to get protected by allied forces and to reorganize for a reconquest of the lost territory. The retreat was characterized by long walks through hardly accessible territory as well as heavy civilian and military loses on the way. Cockburn witnessed these problems by herself when she walked from Kosovska Mitrovica to Prizren “thru snow and mud” (Hart, 1916).

Later, she was evacuated by ship to the Italian city Brindisi. After her experiences she also lived for a while in Paris before she finally moved back to Canada. After coming back to Canada, she worked as a physician in Regina, a town in Saskatchewan. During her time in Serbia, she met the orphan Konstantin Protić and took him to Canada, where this child from Kraljevo got the opportunity to grow up and educate in a protected environment. In the newspaper article he is described as a promising 15-year-old boy, learning the Trade of Mechanist at the Metallic Roofing company. The company officials were also asked for a statement and expressed a great content with him. The article ascribed to him the potential to become “amongst our most valued citizens” (Hart, 1916). He later served in the Canadian army during World War II.

List of sources

Brasme, I. (2021). A Nurse in the Great War: The Exceptional Voice of Mary Borden. Miranda, 23. https://doi.org/10.4000/miranda.42228

Hart, M. L. (1916, March 5). Toronto Woman Doctor Went Thru Serbia With Refugees. The Toronto World.

Stobart, M. A. (2004). The flaming sword in Serbia and elsewhere. Imperial War Museum, Department of Printed Books. Trinity College Toronto. (1922). Trinity College War Memorial Volume.

vesti. (2015, September 17). Doktorka iz Toronta i siroče iz Kraljeva.